on mischaracterizing the criticism of art

reception theory, parasocial relationships, and the consequences

i’ve been hearing lots of stories about people criticizing the criticism of art:

“you don’t have to listen to her”

“just don’t watch it”

“why does it need to be perfect, why can’t it just be fun”

“you’re talking about her — she’s already won.”

“why can’t something just be?”

“the artist should be able to do whatever they want.”

i believe we behold above the many faces of fallacies.

a dear friend of mine who’s a professor at a college in texas and a upenn alum captured my feelings towards it perfectly:

“something is always worth writing about if you have thoughts and analysis. the ‘am I making a mountain out of a molehill’ conversation, imo, is relevant only if you’re trying to cause outrage. in this polarized environment people think you must either love something or be outraged by it, so people sometimes react negatively to good faith criticism. we gotta push back and keep nuance alive!”

inspired by this, i want to write about the concept of keeping nuance alive by deep -diving into the many pushbacks of the “art-police police” or the “critique of the critique” if you will.

“you don’t have to listen to her”

criticism is an integral part of art’s existence. interpretation and evaluation of art — even harshly — is part of the artwork’s life. anyone who might have studied art history would know how essential a part it is. the first lesson almost always asks: who decides what art is?

the typical answer is: “art is art when someone says it is.”

which is what someone said to me when i was giving an art history presentation at the getty museum to a group of adult visitors.

in answer, inspired by the movie mona lisa smile, i pointed at the piece of art we were looking at, and said, “this is art.” they laughed but had they seen the movie, the response should have been: “well, it matters who says it!”

having taken numerous classes in art history and english, i’ve learned that the relationship between art and audience is far more complex than people admit.

thinkers like stuart hall — founder of british cultural studies — and hans robert jauss, pioneer of reception aesthetics, both emphasized that audiences are not passive recipients but active interpreters, their readings shaped by their unique cultural, social, and historical contexts. therefore, critical engagement with art is not parasitic but constitutive of art itself.

this framework of literary criticism is called reception theory. it reminds us that a work of art is never complete until it is received. meaning does not live inside the artwork alone, but emerges in the space between creator and audience — through our expectations and cultural contexts.

these responses are extremely important and help keep the artwork alive, often, as you’ll read below, by reshaping its meaning through the ages.

by releasing something publicly, the artist implicitly meant to invite engagement, including any form of dissent that might give them insight into the exact impact of their work.

think about it: if you wrote a book — would you want someone to own it and never touch it, never draw on it, never write on it? wouldn’t you want someone to engage with it fully, piece it apart? annotate it? underline it? highlight it? talk to you, the author, in the margins? agree with it, disagree with it, engage? that’s an artist’s dream.

that so many people are guilty of trying to protect an artist from that — might actually be a mirror to some form of unconscious insecurity or the like. maybe the like of parasocial relationships. i don’t know. and i’m not interested in that.

what i’m interested in is dissecting what happens when we stop people from criticizing altogether.

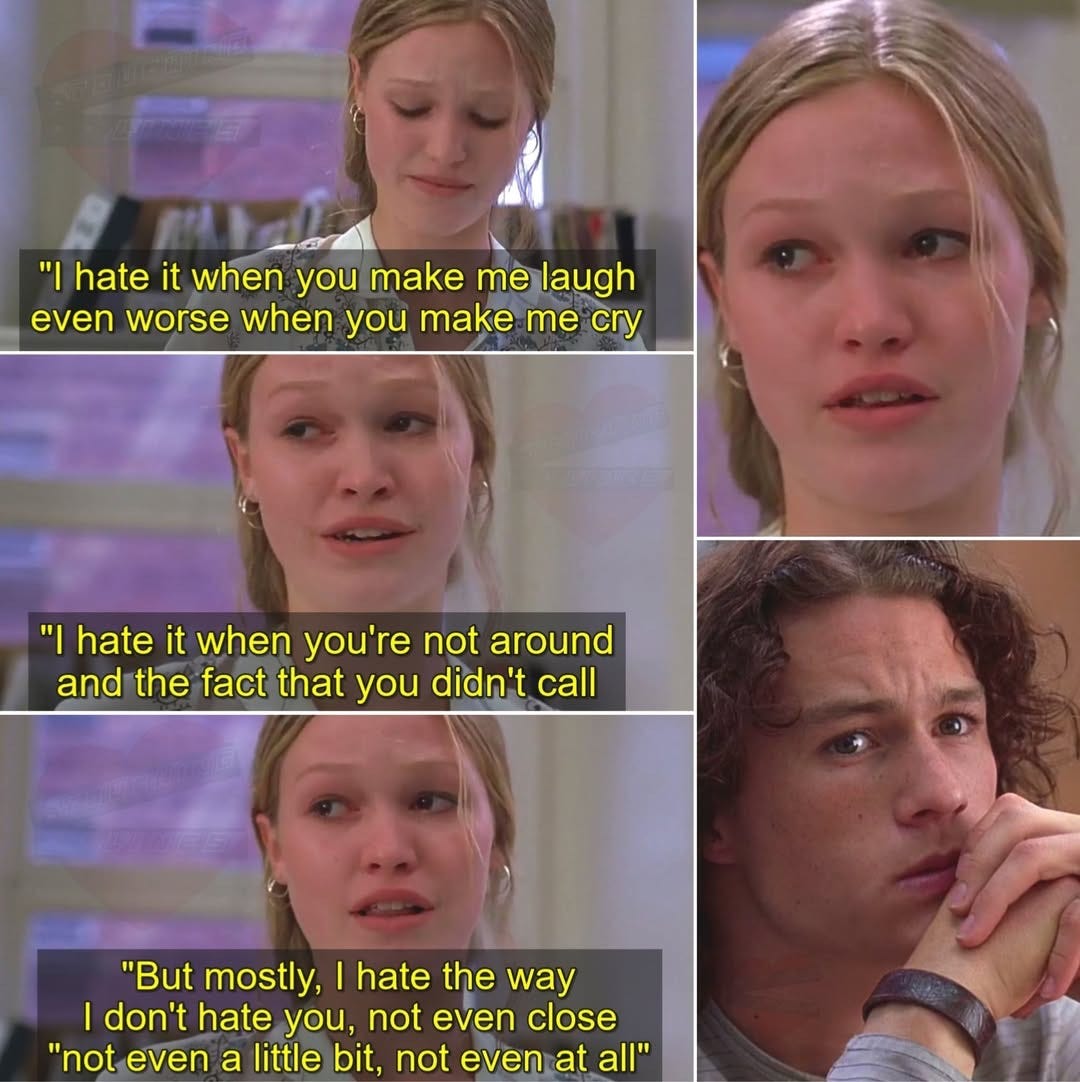

here’s the iconic scene that I had the privilege to relive, btw:

a case study in reading and misreading

stuart hall describes all media as encoded with ideology by its creators, and then decoded by its audience.

the audience’s decoding can take one of three forms:

preferred reading: agreeing with the creator’s intended message

negotiated reading: partially agreeing, but adapting to personal context

oppositional reading: understanding but rejecting the intended message

so if the artist encodes certain meanings into their work — what hall called the “preferred reading” — fans who align perfectly with that message adopt that unquestioningly. meanwhile, critics may take a “negotiated” or “oppositional” stance. the friction between these readings is not a bad thing, and in fact, it can prove really important.

take the following lyrics that a brilliant friend mastering in psychology at pepperdine pointed out to me:

“did you hear my covert narcissism i disguise as altruism like some kind of congressman?”

anti-hero

taylor swift

now, her saying she’s a narcissist is likely meant as a witty confession about ego and self-loathing — and at first glance, harmless. but this flirts with a psychological term that actually describes real patterns of manipulation and emotional abuse.

many listeners, especially younger ones with limited knowledge, might repeat it, never understanding the term’s gravity, even in their own lives.

it risks trivializing a serious dynamic many people have suffered under. this is where oppositional or negotiated reading can become useful. words from pop culture travel, and it’s important to learn how they teach audiences what to normalize or mock.

when I first heard the song, I glossed over it and would not have noticed until someone critiqued it.

jauss explains this with the “horizon of expectations” in his 1982 essay toward an aesthetic reception.

audiences bring their own cultural context to every work. what was once interpreted one way can evolve — or devolve — over time.

this explains why when i was a kid, i loved sixteen candles and now realizing as an adult its casual depiction of sexual assault culture and racial stereotype.

i’m not boycotting but pointing out that we can be nuanced enough to be honest about things and still indulge in whatever we feel like indulging in.

art is important. it influences how people form ideals of social class, gender, justice, and morality.

caustic or not, criticism helps reveal the contradictions and social truths embedded in art. it does not need to be mean-spirited (although i concede that plenty of people are). but a true purveyor of art compares, contrasts, connects — traces effect.

let’s say someone outright “hates” a taylor swift album. that too can teach us something, if they can articulate why — let’s say, through feminist music theory, class analysis, and narrative analysis. this allows us to learn and think deeply about the sociology of contemporary music, and how it affects our lives.

criticism is what keeps those horizons shifting, helping society recalibrate meaning as our values evolve.

“just don’t watch it”

bell hooks, in reel to real: race, sex, and class at the movies (1996), warned that refusing critique reinforces dominant ideologies.

likewise, laura mulvey’s landmark essay visual pleasure and narrative cinema (1975) shows how analysis reveals the hidden power structures within film.

to tell someone, “just don’t watch it” assumes disengagement is the simple antidote if something’s bothersome. why not explore why it is so?

silence can allow all sorts of problematic ideas to circulate unchallenged.

if we love an artist’s work, why be afraid to open it up to scrutiny? do we worry someone disliking what we love means they dislike us?

we must not fold an artist or their work into our identity — when we don’t know the artist. we may not like them if we did. (think ellen degeneres — a friend of mine developed a stomach ulcer working for her team after being a long-time fan.)

thoughtful criticism is one of the highest forms of engagement. it shows the art resonated deeply enough to provoke discourse.

so we must do our artist a favor, and let the criticism flow, and understand the lived experiences that shape it.

we all see the world differently, and intelligence lies in recognizing those perspectives. cultural ecosystems depend on this diversity.

without critics, everything collapses into fan culture — or worse, marketing.

“why does it need to be perfect, why can’t it just be fun”

fun and perfect are not opposites. albums and movies have managed to be both — fun yet formally tight, thematically rich, and morally aware.

do people truly love imperfection in the spirit of wabi-sabi? or are they uneasy when someone else notices what they chose to ignore, or didn’t notice?

aristotle’s poetics reminds us that pleasure in art arises from structure, catharsis, and coherence — not in spite of them.

to dismiss the need for perfection in favor of “fun,” and to frame it as “you’re the serious one, i’m the fun one,” absolves artists — and ourselves — from artistic discipline.

we often confuse carelessness with authenticity. scrutinizing the quality of art can help us recognize if we’re being fooled.

lastly, is fun a shield for everything? bell hooks and angela mcrobbie have both written about how “fun feminism” or “pop feminism” often masks regressive messages under irony.

take emerald fennell’s films:

i’ve never liked them and i can tell you in details why. for one, she is great at hiding ethical incoherence with style and exposition. i’m not bothered by any latent conservatism or classism that might be in her work so much as by her formula of “here’s a list of Crazy Things Happening” passed off as art.

critics should always ask: fun for whom? fun at whose expense? fun toward what end?

thinking is joy. by hearing sides — we can keep nuance alive.

“you’re talking about her — she’s already won.”

this is a common fallacy — as provoking discourse does not mean artistic success.

the idea that “starting a conversation” equals victory — no matter the substance of that conversation — bears no philosophical truth. in fact, in media studies, this is known as the “discourse fallacy”: mistaking attention for merit.

“starting a discourse” can mean you’ve made something polarizing, not profound. controversy is not the same as meaning.

to put it bluntly: if all that matters is “we’re talking about it,” then we’d have to call every propaganda film and viral scandal a masterpiece.

when a pop album floods social media, that’s proof of visibility in an attention economy — not of artistic depth.

what matters isn’t whether discourse happens — but what kind. one can deepen understanding and challenge assumption, and refine taste. the other can be a commodification of outrage, as my friend pointed out early in the essay.

we’re not playing someone’s marketing game by engaging critically — but rather exercising cultural literacy.

hate, actually

to think critically is not to be cruel. it’s to care about what we consume and what it says about us.

my friends and i are passionate about art, and the conversations it inspires. this is a defense of that passion.

to engage deeply with what we love and dislike is respect — for art, intellect, and the world it mirrors.

the idea that silence and uncritical enjoyment are virtues, deserves critique itself.

study or read more on this topic

p.s. you can find copies of the books at dear jane bookshop. proceeds from purchases go towards supporting independent bookstores.

books:

hans robert jauss, toward an aesthetic of reception (1982)

bell hooks, reel to real: race, sex, and class at the movies (1996)

angela mcrobbie, feminism and youth culture: from jackie to beyoncé (2009)

theodor adorno, aesthetic theory (1970)

henry jenkins, textual poachers (1992)

john fiske, reading the popular (1989)

aristotle, poetics (penguin classics)

essays:

stuart hall, “encoding/decoding” (1980)

laura mulvey, “visual pleasure and narrative cinema” (1975)

roland barthes, “the death of the author” (1967)

documentaries:

the great hack, american factory, the act of killing, the century of the self, hypernormalisation, the social dilemma, manufactured landscapes, exit through the gift shop, the four horsemen

films:

the truman show, perfect blue, tár, they live, parasite, black swan, network, fight club, velvet buzzsaw, the lives of others, american psycho, the king of comedy, sorry to bother you, her, ex machina, the social network, dr. strangelove, black mirror

That is a well-crafted essay.

Overall, the process of creating, understanding and discussing artworks (movies, books, music) is extremely subjective. However, I also believe in objective beauty where you know it when you see it (speaking of art). Of course, we can call certain things popular (we can even worship them), but it does not mean that they fall under the category of beauty that awakens a connection to something divine (as a source of that true beauty).

At the same time, I agree that humans can train their sense of perception, cultivate their minds and learn to enjoy artistic expressions that are more complex and profound than products of mainstream media.

I have a friend who told me about "loving critically." I can't imagine real and deep love of any kind without criticism (not what it is mistaken for but what it really is supposed to be). I very much appreciate this post. Our society is too confused about it, like you stated.