the weekly reading guide (vol. 7)

(dec 15 - 21) — essential essays, op-eds, and discussions

NOTE: This is the penultimate guide of the year. Next week’s edition will be a comprehensive roundup of the best op-eds and essays of 2025.

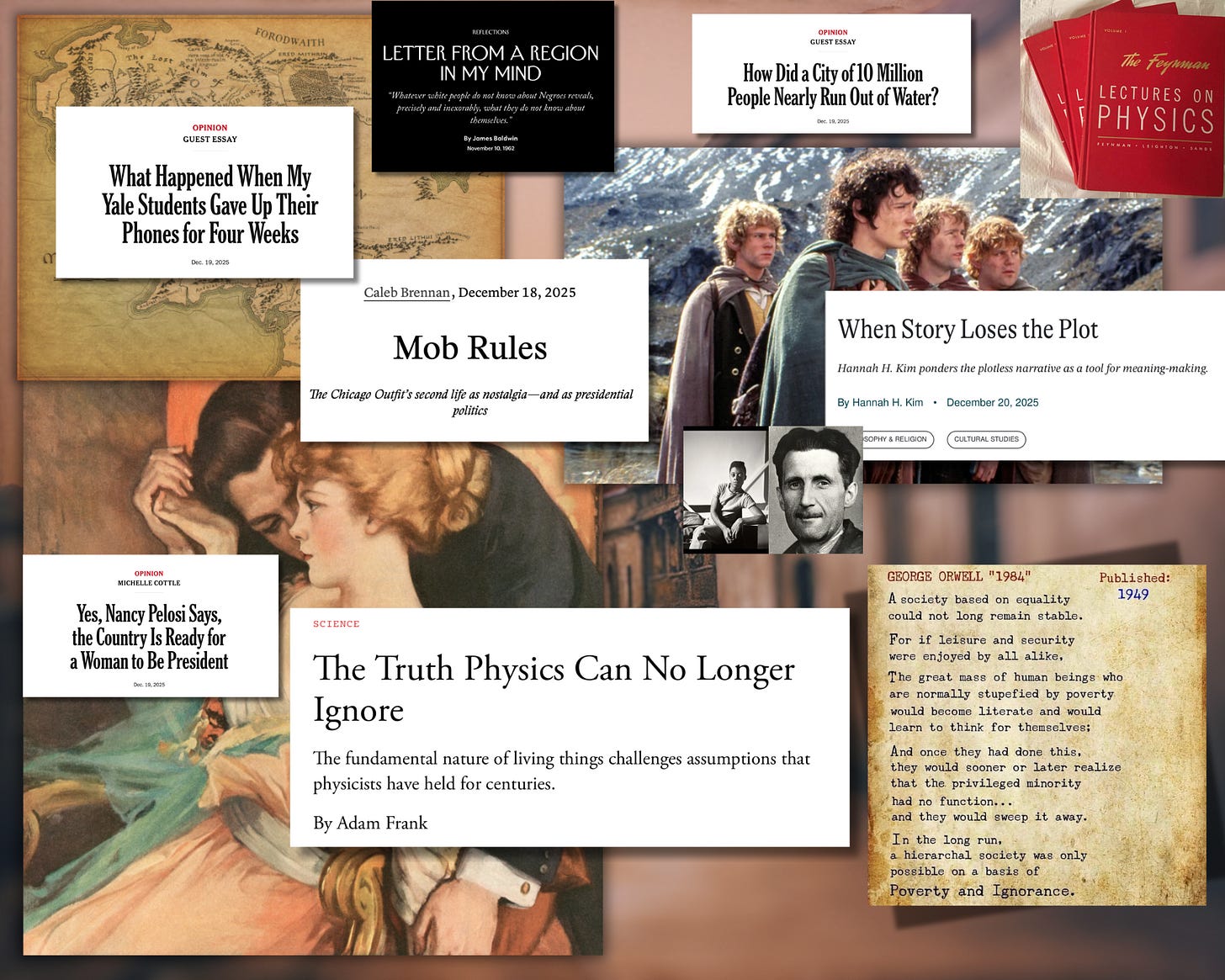

Featured this week:

Orwell on how language corrupts thought; Baldwin on Shakespeare, faith, and cultural ownership; why physics may need to rethink life itself; what happens when story loses its authority; an experiment in living and learning without phones; faith, power, and the dangers of moral certainty; water scarcity as a structural limit, not a technical problem; returning to Tolkien on meaning and mystery; and why we continue to romanticize power through mob mythology.

This week’s list spans The New York Times, The Atlantic, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, The New Yorker, and The Baffler — both free and paywalled.

About The Weekly Reading Guide series: Includes the best pieces of writing — essays, op-eds, and articles — from great and rare corners of the internet and media that are often overlooked. If you don’t have time to scour online newsstands, are tired of the same circulating stories, and want to stay up-to-date on current cultural, social, political, literary, and artistic conversations and discourses, I hope you find this series useful. This Week’s Classic Essays section includes two essays from the canon, paired with guiding questions for deep reading and to mix up current reads with foundational texts.

Read previous week’s guide:

More from the slow philosophy

Monthly Postcards series: Each month, I share an archive of journal entries, mini-essays, and curated art, books, films, poetry, and music. Read the latest:

Letters series: Every quarter, I share a thematic syllabus for deeper living, reading, and self-study. Read the latest":

[Dec 15 - Dec 21, 2025]

Preface: It has been reported that we are living in an era of cognitive and literacy decline. We need to work together to normalize content that protect us from the brain rot of the modern scroll, depleting critical thinking skills, the fading practice of deep reading, and the general decline of the humanities — none of which we can afford. As part of the good fight, I have been putting together these weekly reading guides as well as monthly postcards with curated recommendations of the most nourishing, expansive media content I encounter.

This Week’s Classic Essays

Politics and the English Language - George Orwell

Orwell was a war correspondent & a prominent literary editor before dominating fiction. This is one his most enduring essays. He writes about how vague, inflated, and dishonest language corrupts political thought, and argues that sloppy writing both reflects and enables bad thinking, especially in politics, where euphemism and abstraction are used to hide what’s really underneath it all: cruelty and lies. Clear language, he insists, is not just a stylistic choice but a moral and political act. Well, he did write 1984! Thanks, George Orwell.

Why I Stopped Hating Shakespeare - James Baldwin

Baldwin is the most poetically masterful essayist I have ever read. Here, he revisits his early resentment toward Shakespeare as a symbol of cultural exclusion and colonial authority — which makes sense because we might love Shakespeare but the man WAS Elizabethan — and explains how he eventually came to recognize Shakespeare’s deep understanding of human complexity. Baldwin-style, he eventually reflects on education, power, and ownership of culture, arguing that great literature belongs to anyone willing to confront its truths. Baldwin is the reason I have been able to read classical authors at all — despite their problematic viewpoints.

Bonus:

Letter From A Region In My Mind - James Baldwin

I had to include this one not only because it’s Baldwin’s best work, but it might be one of the best essays ever written — period. A deeply personal piece on faith, race, and identity, this essay introduced me to the magical world of Baldwin’s writing. He traces his early involvement with the church and his eventual rejection of organized religion. Through intimate reflection and moral urgency, he explores how religion can both uplift and imprison, and how America’s racial crisis is inseparable from its spiritual failures. This essay, and his prose, will give you chills.

Now, onto the contemporary.

Last Week’s Best Pieces of Writing

Note: My guides span every corner of thought. Each brings its own light. The aim is to read widely, think critically, and notice where ideas meet and where they part. No school of thought should be a fan club. Accountability, nuance, and the ability to take compassionate, principled stances are the only grown-up postures in life, society, and culture. Let’s think for ourselves and find common ground.

The Truth Physics Can No Longer Ignore - The Atlantic

The article argues that physics can no longer ignore life as something fundamentally different from inert matter, because living systems challenge long-held assumptions about how the universe works. Traditional physics relies on reductionism — the idea that everything can be explained by breaking it down into particles and laws — but life behaves as a self-organizing, evolving process that can’t be predicted from its parts. Living things maintain themselves, use information for their own goals, and act autonomously in ways machines do not. New approaches from complexity science suggest that “more is different,” meaning higher-level systems like organisms have emergent properties that physics alone can’t reduce away. Understanding life this way could help explain how life began, how to detect it on other planets, and how to think more clearly about intelligence and AI. Ultimately, the author suggests that studying life may reshape physics itself, pushing it toward a more collaborative, interdisciplinary future.

When Story Loses the Plot - Los Angeles Review of Books

The essay argues that contemporary culture is moving away from traditional, plot-driven storytelling toward other ways of making meaning, such as mood, character types, identity labels, and games. A decade ago, “storytelling” was treated as the key to understanding everything — from politics to personal identity — but critics have since warned that stories can oversimplify reality and impose false coherence. Today’s fast-paced, fragmented media environment, combined with shortened attention spans and constant information flow, makes sustained narrative arcs harder to follow and less persuasive. As a result, many films, TV shows, and cultural forms now downplay plot and instead focus on atmosphere, emotional texture, or recognizable character archetypes. These alternatives still provide orientation, meaning, and satisfaction, even without clear beginnings, climaxes, or resolutions. The shift suggests that while humans still need narrative to make sense of life, we are experimenting with new structures that feel better suited to a world marked by uncertainty, distraction, and skepticism toward neat endings.

How Did a City of 10 Million People Nearly Run Out of Water? - The New York Times

The title of this op-ed felt haunting to me so I just had to read it. How does this even happen? The writer explains how Tehran, a city of 10 million people, came close to running out of water due to a mix of severe drought, climate change, rapid population growth, and poor water management. Climate change has made the region hotter and drier, reduced mountain snowpack, and caused rainfall to come in short bursts that don’t replenish groundwater. That said, he says human factors matter just as much: decades of underinvestment in infrastructure, widespread illegal wells, overuse by agriculture, and explosive urban growth have pushed water demand far beyond sustainable limits. The author’s main point is that Tehran’s water crisis can’t be solved by clever fixes or dramatic gestures like moving the capital to a new location. Those ideas sound bold, but they avoid the harder truth: the city has grown far beyond what its environment can support. Tehran doesn’t just have a temporary shortage — it has a structural problem. There simply isn’t enough water available, year after year, to sustain so many people, farms, and industries at current levels. Drawing on historical examples of cities that collapsed after mismanaging water, the essay warns that modern cities are not immune to natural constraints and must learn to live within them rather than assuming technology can always prevent disaster.

Christianity Is a Dangerous Faith - The New York Times

From conservative columnist David French — the title is more sensational than the argument itself. The column actually argues that all religions become dangerous when it is practiced with absolute certainty and a hunger for power, because that mindset can justify cruelty toward others in the name of righteousness. David French contrasts this kind of fundamentalism with what he sees as true Christianity, which is rooted in Jesus’s humility, vulnerability, and rejection of political dominance. Jesus was born poor, lived without worldly power, and refused to lead a political revolution, instead teaching love of enemies and service to others. French says many Christians often ignore this and instead pursue control, condemnation, and cultural victory. In his view, Christianity properly lived demands self-sacrifice, refusal to hate, and resistance to the urge to dominate others, even when doing so is politically or socially costly. That’s a framework that should apply to every religion — as well as secular ideologies.

What Happened When My Yale Students Gave Up Their Phones for Four Weeks — The New York Times

Describes a Yale instructor’s experiment requiring students to give up their phones and internet access for four weeks during a study-abroad course in France, and the surprising benefits that followed. Rather than resisting, students welcomed the break (who wouldn’t?!) and quickly noticed dramatic improvements in focus, sleep, creativity, and confidence. Free from constant digital distractions, they wrote more deeply, read faster, rested better, and rediscovered play, conversation, and sustained attention. The author argues that today’s students are not incapable of concentration but overwhelmed by addictive technologies and poorly designed academic systems that demand constant connectivity. She concludes that colleges should create structured, collective offline spaces — phone-free programs, dorms, or campuses — to give students the conditions they need to think clearly, learn deeply, and reconnect with their intellectual and creative capacities.

Making Sense of Middle Earth: Exploring the World of J.R.R. Tolkien - Literary Hub

The essay reflects on how J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings shaped the author’s childhood and explains why these books feel so powerful and different to so many readers. He describes first encountering Tolkien through confusing images, unfamiliar names, and incomplete explanations, and argues that this sense of mystery — having to piece together a world from fragments—is central to Tolkien’s lasting impact. Rather than being a flaw, the gaps, contradictions, and unfinished feeling of Middle-earth draw readers into actively making sense of the story, much like learning about the real world. For the writer, these books became intertwined with memories of comfort, fear, illness, and family, giving them deep emotional weight. He suggests that Tolkien’s uniqueness comes not from any single element, but from a combination of storytelling, scale, and discovery — especially how The Lord of the Rings transforms The Hobbit into the first glimpse of a much larger, richer world that readers learn to understand on their own.

Mob Rules - The Baffler

The essay reflects on growing up near the site where Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana was murdered and uses that memory to explore how the Chicago Outfit once wielded enormous power over labor, politics, and everyday life. It explains how figures like Giancana and Al Capone have since become romanticized folk characters, remembered less for their violence and corruption and more for myths about loyalty, order, and helping the community. Through interviews with descendants of mobsters and victims, the piece shows how nostalgia glosses over the reality that the mob thrived by controlling unions, colluding with politicians and law enforcement, and violently suppressing threats. It argues that this sanitized fascination with gangsters reflects a broader longing for a brutal but predictable system under capitalism, and helps explain why modern reactionary politics sometimes echo mob-style ideas of power, loyalty, and “law and order,” even as the real human cost fades into the background.

Critical Thinking

1. language, story, and power

how do language and narrative shape what we are willing to see, excuse, or ignore — in politics, religion, science, and culture? where do euphemism, simplification, or myth-making replace moral clarity, and who benefits when they do?

(orwell; baldwin; lrb; baffler; french)

2. imitation, attention, and discernment

where do these essays show imitation — of belief, certainty, taste, or authority — taking the place of independent judgment? how do attention, reading habits, and media environments shape our ability to think clearly and resist consensus thinking?

(orwell; yale phones; lrb; tolkien)

3. limits, humility, and meaning

several writers resist neat explanations — whether about life, cities, faith, or fictional worlds. what changes when we accept limits instead of mastery, and humility instead of certainty? how might this reshape how we think about progress, power, responsibility, and meaning?

(atlantic physics; nyt water; tolkien; baldwin; french)

How am I just finding this? Can't wait to stay up-to-date with all these future posts!!!

look forward to your breakdowns every week, it's like my newspaper <3